Accretion Room, Moana Project Space

Download the exhibition catalogue (PDF)

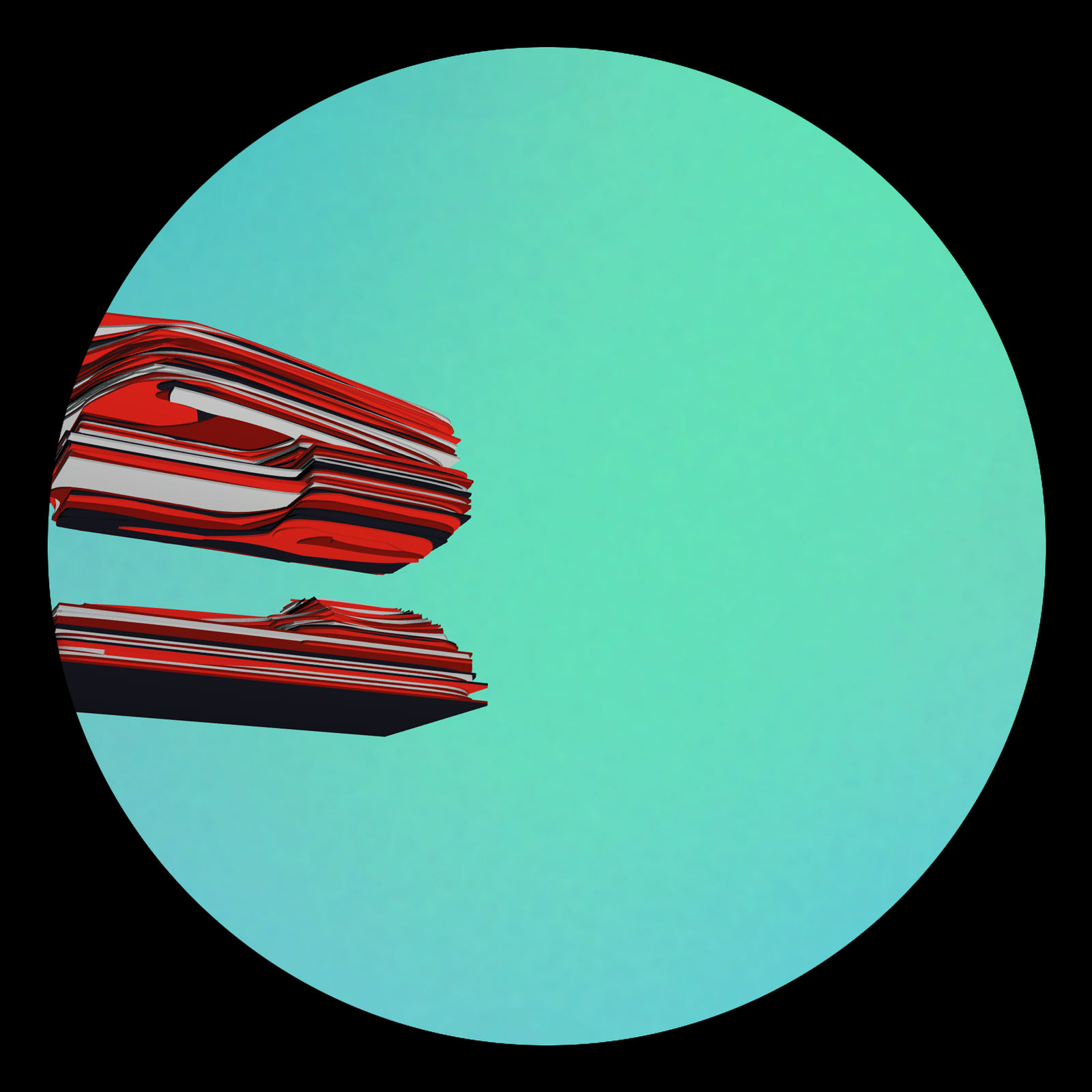

This interactive installation work comprises a computer-driven motion sensor, speakers and projector. The projection shows 3D geological strata accreting and eroding in real time. The computer tracks your movements around the space and uses the resulting data to change the patterns of accretion and erosion in the projected forms.

Accretion Room is showing at Moana Project Space in the Perth CBD from 3–26 July, 2015. Its purpose is to explore, in real time, the interaction between people and simulated geological forms.

On entering the installation you will see a room painted matt black, with a circular projection screen at one end showing striated geological forms. As you move around the room, the forms will erode and accrete in response. Subtle sounds will accompany these changes. You’ll be able to play with the work, but the interactions will be nonlinear in nature, preventing any real sense of control.

Background

This work comes from a series started during my 2013 residency in Cossack, a ghost town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. (The residency was part of my prize for the 2012 Cossack Art Award). While there, I became fascinated with the geology of the region.

Geological timescales are unimaginably vast and the processes are often slow and indiscernible, so we tend to think of geology as something that exists independently of life. However, this is an illusion: the interactions between our planet and the life that lives on and within it are complex.

There are two good examples of this interaction between life and the planet, widely separated in time: the first very early in the earth’s history, and the second in our own time.

The first is early banded iron formations, formed around 2.5 billion years ago by the first photosynthesising life in the oceans. The resulting oxygen eventually made the sky blue for the first time and caused insoluble iron oxides to precipitate out of solution to the sea floor—building the striations we see today in the Pilbara. These formations include the Hamersley Ranges, and it is from these deposits that both the prized hematite iron ore at Mt Tom Price and the deadly asbestos at Wittenoom have been extracted. So this ancient phenomenon—called the Great Oxygenation Event by geologists—has a very tangible impact on our life in Australia today.

The second is our own effect on the planet. We are causing many changes, of which global warming is only the most worrisome. Cumulatively, these changes are sufficiently profound that many scientists have proposed the term Anthropocene (from the Greek roots anthropo-, meaning “human”, and -cene, meaning “new”) to describe the epoch that we are living in.

The interactions between life and the planet lead to unpredictable results. Accretion Room is neither an illustration of the Great Oxygenation Event nor the Anthropocene: instead it takes elements from both to form a work that runs in parallel. The living visitors to the installation are an integral part of the work; the resulting formations are also intrinsically unpredictable.