The worlds of Sie and du

I only learnt German at high school for three years; I enjoyed it, but it was far from my strongest subject. My father spoke German like a native speaker and my parents (who were both from Melbourne, by the way) would sing us lullabies in German when my brothers and I were small. So I’ve always been in the curious position of having an emotional attachment to a language I never spoke well, a slight sense of shame at disappointing my father by not mastering it, and the additional irritation at having since forgotten a great deal.

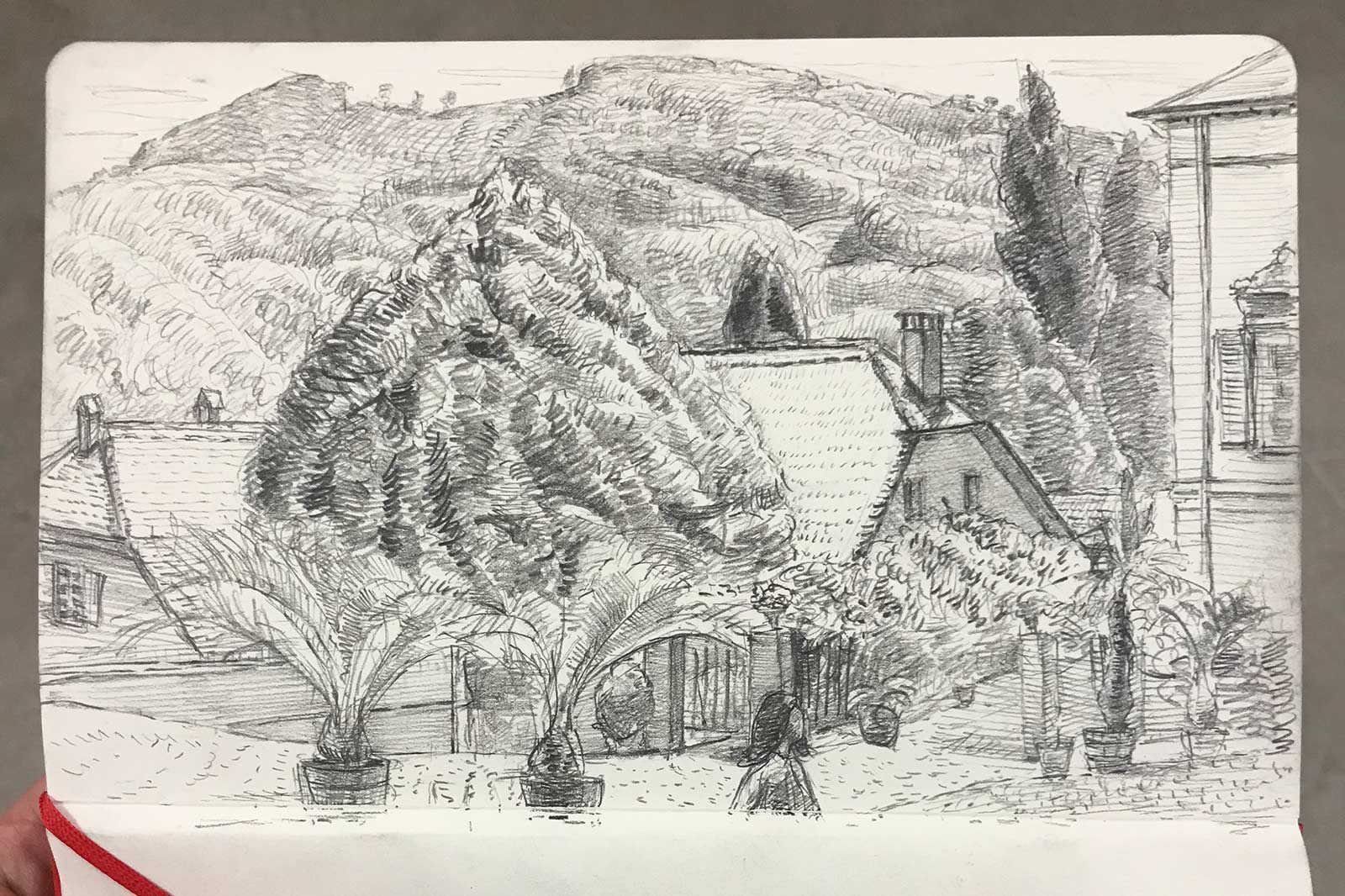

As if to confirm my theory that almost everything you learn becomes useful at some point, I’m now in Basel, Switzerland on a four month residency at Atelier Mondial, supported by Artsource. It’s a German-speaking region. While it is true that most people speak English, and sometimes to a very high standard, it’s certainly not true of everyone you meet. So it’s useful — occasionally very useful — to know some German. However, that wasn’t my primary motivation in trying to pull my rudimentary German into something more usable. For one, I’ve always felt that there’s something a little shameful, even rude, in relying on the global dominance of English as a lingua franca.* For another, I’ve long suspected that speaking a language with its native speakers — especially on their home turf — can give you a perspective on their culture and mentality that is otherwise unavailable to you. I had a remarkable experience a few days ago that seems to bear out this hypothesis.

To give a little background: you might know that in German, as in French and (I imagine) most other European languages, there are two different ways of saying “you”. Which one you use depends on your relationship with the other person. To someone you don’t know, or with whom you have an otherwise formal relationship, you use the formal mode of address: to say “you”, you say Sie. It’s only with friends and family that you use the informal “you”, which is “du”. My perception of this arrangement was always that Sie — the formal “you” — was essentially a distancing measure, a way of keeping other people at arm’s length. We don’t have this arrangement in English; surely saying “you” to everyone is friendlier, more egalitarian?

Fellow Perth artist Rina Franz and I were having dinner with some lovely Baslers we had met a few days earlier. (Rina is also doing a residency at Atelier Mondial.) The conversation was in a mix of German and English. Obviously, when I met these people I had been careful to address them as Sie. During the course of the meal, however, I noticed that at some point we had all switched to the informal du. Perhaps it was just the wine, but at that point I experienced a new feeling: a sense of warmth and inclusiveness, a sense of being part of “us” — this group of people now on friendly terms. It was a bit like finding that I was a member of a new family, but without any awareness of the transition.

So my perspective on this feature of German — which I had always disliked — was changed. I have no doubt that using Sie is a way of keeping others at arms length. But there’s a lot more to the picture. You can transition from the hard-edged world of Sie to the soft and cosy world of du. Having made this transition, I no longer see the world of Sie as simply icy and unfriendly: I think the better perspective is that it’s a way of showing respect to strangers. To address them as du without having made the proper transition wouldn’t only be presumptuous — it could suggest an infantilising contempt. Because the only strangers you can address as du are children.

* As an aside: I do think it’s a good thing that there is a global language. It’s just that I would prefer it were one that didn’t have the horrible colonial history of English.